Norchia:

An Etruscan Necropolis

The City and the Necropolis

Norchia was founded towards the end of the 4th century BCE as a stronghold to protect the powerful Etruscan city of Tarquinia. The city was created and financed by members of the Tarquinian aristocracy, who owned large swathes of the land in the area.

In times of peace, the inhabitants of Norchia devoted themselves to exploiting the land (farming, stockbreeding, forestry, etc.) but in times of war, they took part in the maneuvers of the Tarquinian army, defending their lands against Roman incursions. Over time, a prosperous local elite arose and began to build impressive rock cut tombs in the cliffs of the tufa spurs around the city.

Drone footage of the ancient settlement of Norchia. Video created by Altair4 Multimedia. Courtesy of SABAP-VT-EM.

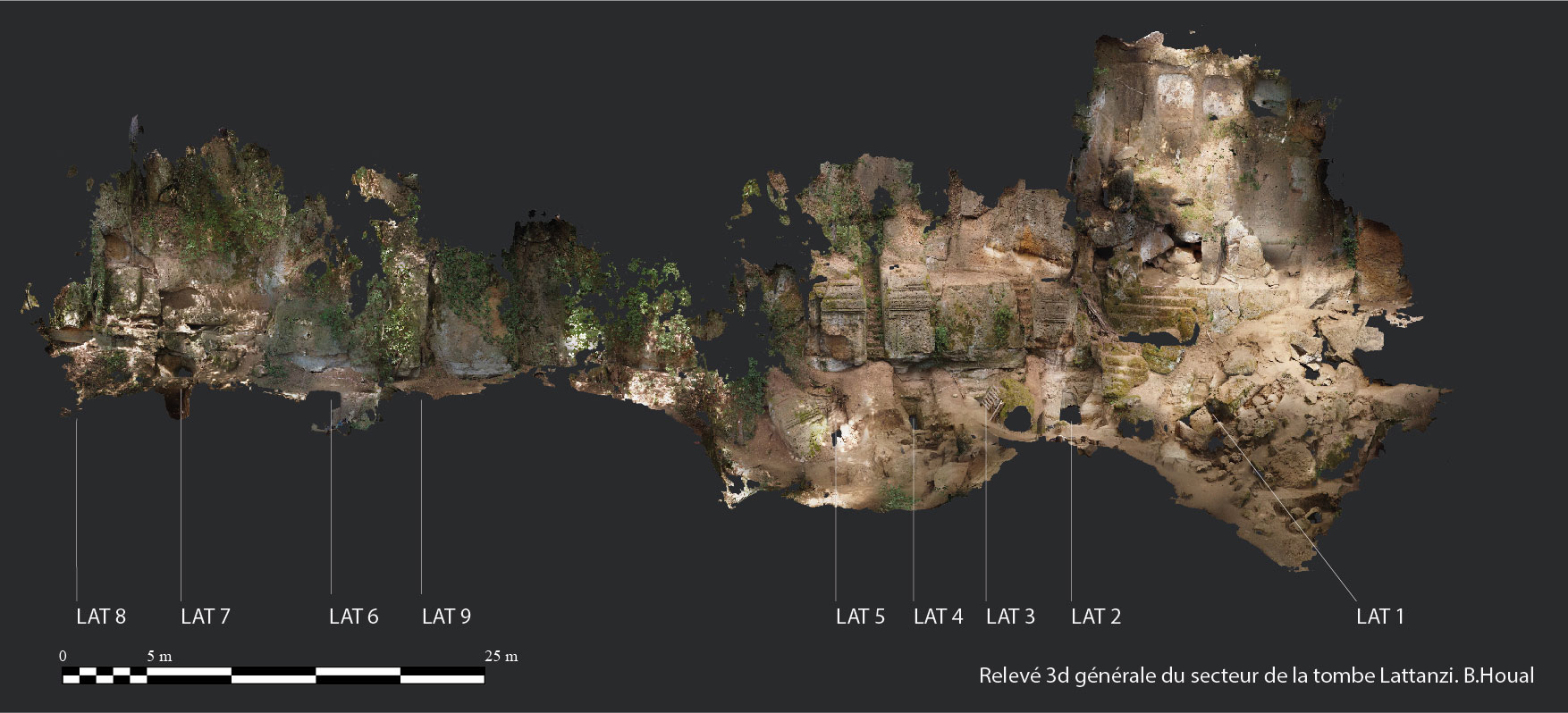

This necropolis is made up of several groups of rock tombs, many of which were collective burial places for families over generations. The largest and most monumental belong to the so-called Lattanzi Tomb group, named after Mariano Lattanzi, the local amateur archaeologist and doctor who first explored them in 1852. The most monumental of these tombs, Lattanzi 1, belonged to a man called Arnth Churcle—who possibly founded Norchia—and his family. The Churcles were one of the wealthier Etruscan families in the community judging by their tomb, which features temple-like façades, colossal sculpture, and a banqueting hall that were highly visible in the landscape and from the city itself.

The Churcles set the standard for tomb design in the Norchia necropolis, and other families emulated their tombs as a form of social competition, vying for visible tomb locations and incorporating monumental facades and sculpture where possible. On top of the cliffs, funerary ceremonies including games and feasts celebrating the dead would have been performed, turning the entire affair into a rowdy spectacle.

The Churcles’ Tomb (Lattanzi Tomb 1)

The Churcle family tomb was accessed via a rock-cut staircase that descended from the top of the cliff. It led down a winding path of different tiers until finally reaching the tomb itself. The upper tier has a monumental facade that resembles an Etruscan temple, complete with pilaster columns, a carved “roof,” and a pediment with relief sculpture. On top of the roof were cut-out slots for the placement of funerary cippi stelae, examples of which you can see in the exhibition. Another staircase leads downward to a columned portico and platform, where visitors are met by a colossal statue depicting a mythological scene of the god Zeus as a bull abducting the Phoenician princess Europa (see Sketchfab Model). Next to it is a banquet hall with doric columns, a false door (resembling a giant T), and stone benches used in funerary feasts for the dead. Above the hall is a relief frieze of griffins and floral designs. We think that the fragment of a sphinx-wing sculpture found in the banquet hall likely belonged to a statue placed on the far side of the hall, mirroring the placement of Zeus and Europa.

A sculpted head that resembles the Macedonian king Alexander the Great was also found in the banquet hall, and likely came from another piece of sculpture placed on that level. Many of these features were originally painted, making them colorful and visible, and much different from how they look today. The tomb is a monumental testament to the Churcle family’s wealth and status in society, and the sculptural elements, particularly the head of Alexander, may allude to influences from Macedonian royal tomb architecture.

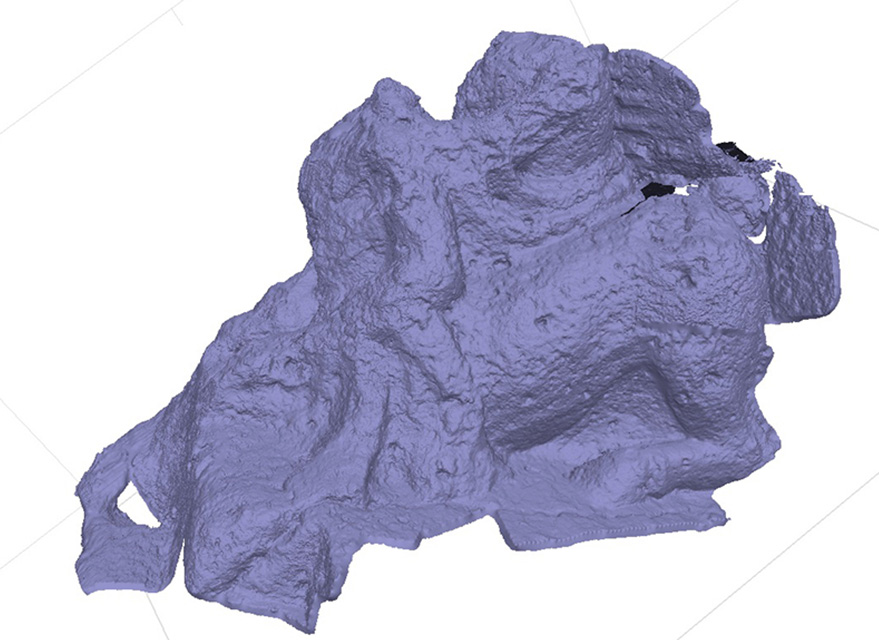

3D rendering of the monumental facade of the Churcle family tomb as it looks today. Copyright of Benjamin Houal.

Reconstruction of the monumental facade of the Churcle family tomb. Video created by Altair4 Multimedia. Courtesy of SABAP-VT-EM.

3D model of the interior of the Churcle family tomb. Copyright of Benjamin Houal.

Below the hall and at the bottom of the staircase was the tomb itself, accessed through a corridor (dromos) cut into the rock, and leading to two simple square burial chambers. Originally, sarcophagi carved from nenfro (a volcanic rock) filled the tomb over generations; when it was initially discovered in the nineteenth century, there were seven sarcophagi in the main burial chamber.

Five of these were removed at that time: Three of these are now lost and only photographs of them remain. The two other sarcophagi were sent to the Museo Rocca Albornoz in Viterbo and the Altes Museum in Berlin respectively, and have carved high relief mythological scenes, Etruscan inscriptions, and lids carved to resemble the deceased lounging on a banquet couch. You can explore these further in the 3D models below.

3D models of the nenfro sarcophagi from Lattanzi Tomb 1 now in the Museo Rocca Albornoz and the Altes Museum (Nr.:SK 1263). 3D models Copyright of Daniel Morleghem.

The Other Lattanzi Tombs

The other tombs in the Lattanzi group are less monumental and smaller in size—clearly ancillary to the Churcle’s tomb—lined up along the cliff face alongside it and using its staircase and banquet hall. They consist of large block-shaped stone faces carved with decorative mouldings at the top, slots for funerary cippi, and a false door in relief in the center. Lattanzi Tomb 3 belonged to the Atie family, and many of the objects in the exhibition come from this tomb, including the stamnos, about which you can find more about below.

3D model of the facades of Lattanzi Tombs 2-4. Copyright of Benjamin Houal.

The burial chambers of most of the tombs were rather plain compared to their decorative exteriors. Some consisted of a single chamber lined with stone sarcophagi, in which the deceased were placed. Others had benches on which to lay the bodies, while others simply had pits carved into the floor that were covered with stone or tile lids.

Up to eighty people were buried in some of the tombs, illustrating the continual reuse of tombs over generations and their strong connection to families over time.

3D model of the interior of Lattanzi Tomb 3. Copyright of Benjamin Houal.

The different tomb types in the Lattanzi group also reflect interfamily dynamics. The monumental Churcle family tomb is the largest and most important and had stone sarcophagi with carved sculptural details.

The ancillary tombs, with plain sarcophagi or simple pits and multiple burials, seem to belong to an extended family of the Churcles or family friends close to them such as the Atie family.

3D model of the temple facades of tombs from the Norchia necropolis. Copyright of Benjamin Houal.

The other family tombs in the Norchia necropolis took inspiration from the Churcles, imitating Etruscan temple architecture and selecting highly visible locations along the cliffs. Several of them also feature carved temple facades with pediments and relief sculpture, and had banquet halls cut into the rock below them near the tomb entrance.

This tradition of rock-cut tombs endured even after the Roman conquest, at the beginning of the third century BCE, as rock tombs continued to be created here for almost two centuries, until the Etruscans were thoroughly integrated into the Roman state. The persistence of these traditions points to the power of family ties in Etruscan society and their connections to the landscape and place.

Building the 3D Models of the Lattanzi Tombs

To create the models of the tombs and the Marce Atie Stamnos presented on Sketchfab, we used photogrammetry, a 3D modeling method that reconstructs an object or site from photographs taken from multiple angles. This technique is most extensively used at the Norchia site, with the help of small drones that allow us to rapidly capture large surface areas.

Progress of the 3D model of Zeus and Europa statue. Copyright of Benjamin Houal.

Cleaning and adding details to the final 3D model of the statue. Copyright of Benjamin Houal.

The first step involves systematically photographing the object or structure, covering all faces at regular intervals and under consistent lighting conditions. Depending on the complexity of the subject, the number of images can range from 500 to 2,000 photos. These images are then imported into photogrammetry software (such as Agisoft Metashape, RealityCapture, or Meshroom), which automatically identifies common points between photos to generate a point cloud and then a textured 3D mesh in high resolution.

The model is then cleaned and optimized using software such as Blender or MeshLab, and exported in .glb or .fbx format for upload to Sketchfab. Once the model is published, annotations, lighting, background settings, and descriptive information can be added. Photogrammetry offers a powerful tool for heritage documentation and outreach, enabling researchers, students, and the general public to explore archaeological remains remotely in 3D, with high fidelity.

The Marce Atie Stamnos

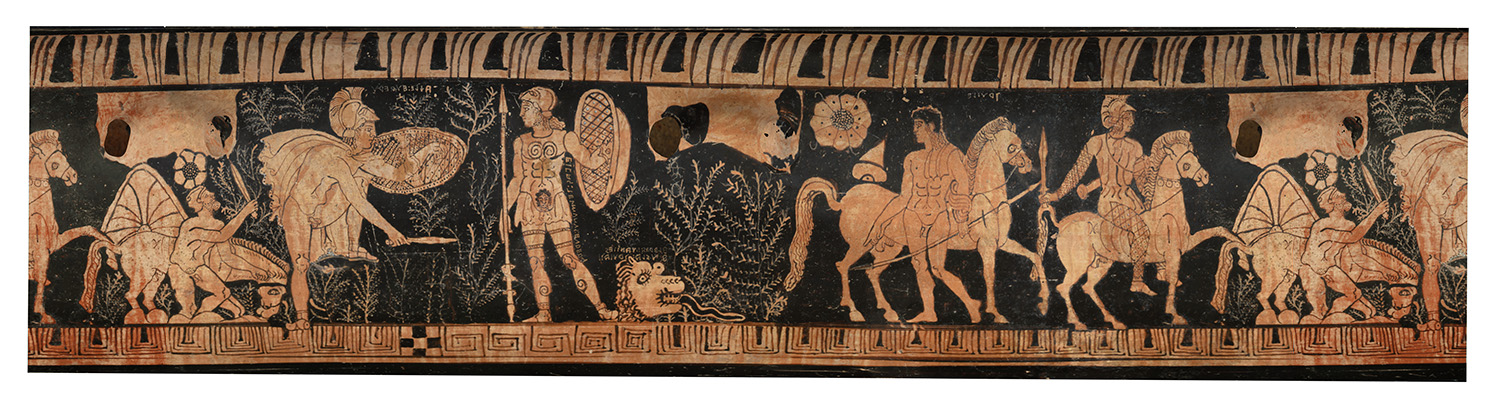

From the eighth century BCE, pottery produced in Etruria was constantly influenced by the various fashions of Greek ceramics. After Greek potters had settled in Etruria and introduced the fast wheel, local Etruscan potters produced their own versions of Greek black-figure and, later, red-figure vessels. The Norchia stamnos, a vase used for mixing wine, belongs to the latter category and is part of a tradition of red-figure pottery that lasted for about a century in Etruria. Etruscan red-figure pottery was a luxury product, initially aimed at an aristocratic clientele who were keen to acquire large pottery wine vases, which were less expensive than bronze tableware and whose painted figurative scenes provided inspiration for lively discussions at banquets.

At the time when the Norchia stamnos was produced in a workshop in Vulci, around 330 BCE, Etruscan craftsmen were increasingly producing vases not only for the aristocracy but also for the middle class. Using the 3D model below, have a look at the inner mouth of the vase, where you can see an inscription running along it that translates as “Marce Atie (son) of Velχae (and) of Paci (or Puci)”—indicating that the vase was commissioned by Marce Atie directly from a craftsman. It was, therefore, Atie who chose the figures depicted on the vase and the accompanying inscriptions.

3D model of the Marce Atie stamnos. Copyright of Benjamin Houal.

The figurative decoration covers the entire surface of the vase but is divided into two sides that can be read, like Etruscan writing, from left to right. On one side, located in the Underworld as indicated by the asphodel (a flowering herb), the vase’s protagonist is Ajax, one of Greece’s most valiant warriors, who is clad in his armor and holds a spear and shield. Behind him is a lion’s head, representing the fountain of Apollo’s sanctuary near Troy.

Facing Ajax is Achilles, brandishing a sword, while the wizened king of Pylos, Nestor, tries to get up from his fallen horse mired in mud. On the opposite face, situated in the land of the living, are the Trojans: Penthesilea, queen of the Amazons, rides with a sword in her hand and wears the distinctive patterned trousers of the famed female warriors; meanwhile Prince Troilos is depicted in front of his horse, looking toward the lion’s head fountain.

Rolled out view of the decoration of the Marce Atie stamnos.

Animation introducing the main characters of the stamnos. Video created by Altair4 Multimedia. Courtesy of SABAP-VT-EM.

But what was the profound meaning of these scenes? On the Underworld side, the vase shows us the truly heroic character, the warrior Ajax, compared to two flawed warriors, the impetuous and quick-to-anger Achilles and the frail and aging Nestor. The characters are thus to be understood as the embodiment of their qualities as well as their flaws. On the opposite side, Penthesilea and Troilus, who share the tragic fate of having been loved and killed by Achilles, are represented a few moments before their death.

All of these characters and the Homeric epic of the Fall of Troy were well-known to the Etruscan aristocracy, who in a sense were reliving the myth in their own fight against the Romans. Placed centrally in a banqueting hall, this stamnos—and its stories—would have inspired conversation in the Etruscan banquets of both the living and the dead.