Poggio Colla:

An Etruscan Sanctuary

The Settlement and Sanctuary at Poggio Colla

The Etruscan sanctuary and settlement of Poggio Colla (modern-day Vicchio) occupied a dominant position at the northern edge of modern-day Tuscany, located along key communication routes over the Apennine mountain range. Built on a high fortified plateau of about four acres, the settlement and sanctuary was occupied for roughly 500 years before its final destruction some time between the seventh and second century BCE.

The fissure at Poggio Colla with a fragment of the first temple that was used to seal it. Copyright of Greg Warden.

The hilltop sanctuary underwent a series of changes throughout its long history. In the seventh and sixth centuries BCE, it took the form of a village of single-family homes constructed with a wooden frame, mud-brick walls, and thatch roofs, a common type of house found across Etruria. The village was built close to a nearby natural fissure that led to a small underground chamber, which remains unexcavated. The fissure and chamber were likely a sacred space connected to a chthonic (underworld-related) cult. The Vicchio stele, a replica of which is featured in this exhibition, appears to have been erected within the sacred complex during this time, and its inscription connects the cultic practice of the fissure, and later temple, to the Etruscan deities Uni (goddess of fertility and family) and her husband Tinia (supreme god of thunder and storms).

This village was destroyed by fire in the mid-sixth century BCE, and a few decades later the plateau was extended to the north with an earthen fill to accommodate a new monumental temple. While only a few pieces of this temple survive, it seems to have been made of carved stone, wood, and terracotta, and likely painted in bright colors. Located high atop the plateau, the divine house of Uni and Tinia would have been a commanding monument across the valley. This temple was destroyed around 400 BCE, but the community ritually buried its remains before a new temple was built over it, illustrating the important connection between the sacred space and the local populace.

Votive Practices

Many of the items found in the sanctuary at Poggio Colla were votive objects, given as gifts to gods with the expectation of divine favor.

While most people would have recited private prayers and provided simple gifts of food, drink, or even small objects at the temple, the wealthy could afford precious gifts such as small copper-alloy figurines or black polished Bucchero pottery. Some of these everyday votive objects can be seen in 3D models below. One of these gifts may have belonged to a pilgrim from southern Etruria named Cavi, who inscribed his name on a small sherd of Bucchero pottery.

3D model of a Bucchero Fragment inscribed with the name “CAVI.” 6th century BCE. ISAW No. 28. Copyright MVAP/SABAP-FI

Certain of the objects discovered in the sanctuary seem to be of a special nature and were found together in pits that were dug into the floor of the temple after its first destruction in 400 BCE. They appear to have been sacred objects that were carefully removed and ritually buried.

These include copper-alloy votive figurines and stone bases used for statuary, perhaps for the main cultic images in the temple. The deposition of these objects in groups and the construction of a new temple on top of them seem to mark a significant moment of both trauma and renewal in the life of the sanctuary and the local community.

3D models of copper alloy female figurines and an inscribed sandstone pyramidal base for statuettes from the votive deposit in the temple at Poggio Colla. 5th century BCE. ISAW Nos 16, 20, 17. Copyright of MVAP/SABAP-FI

The Vicchio Stele

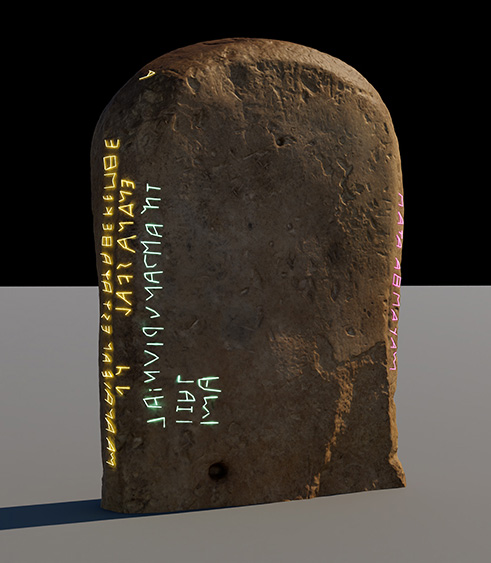

The Vicchio Stele was discovered in 2015 at Poggio Colla and has played a significant role in the ongoing decipherment of the Etruscan language. It was originally on display in the sanctuary before its first destruction around 400 BCE, after which it was ritually buried before the new sanctuary was built. What made the stele truly exceptional was the discovery of a number of long Etruscan inscriptions on its surface, which have provided a wealth of new Etruscan words and grammatical information.

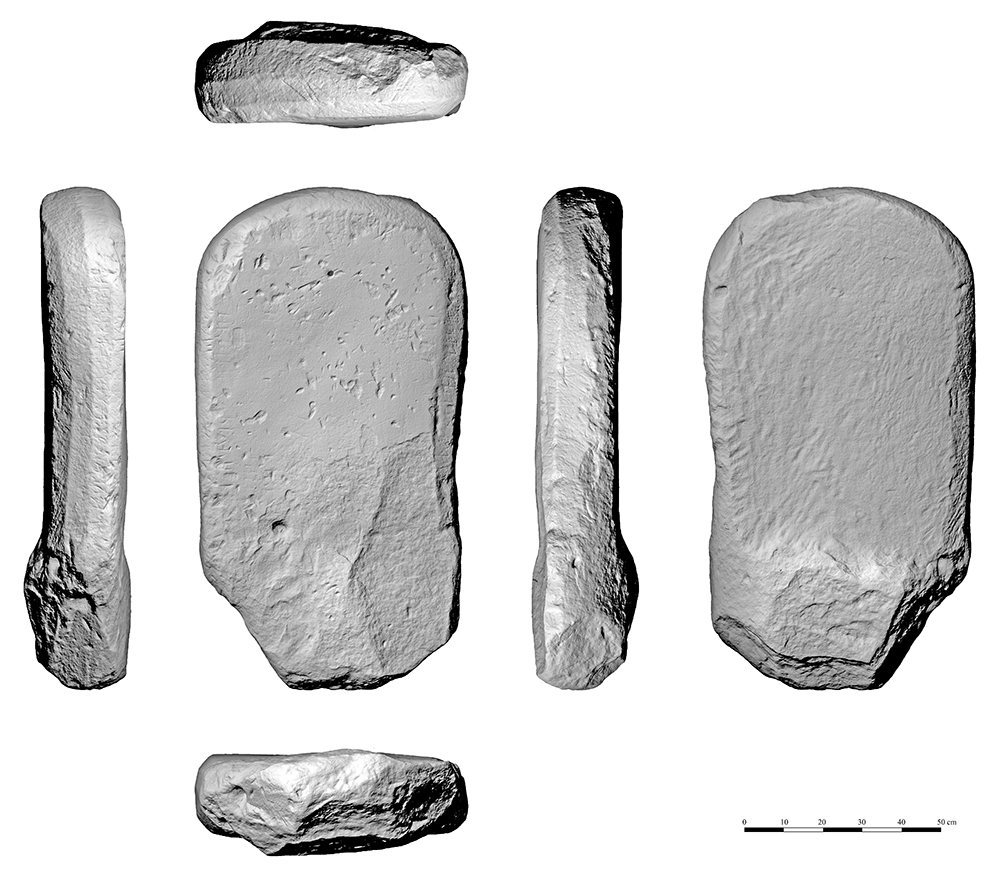

3D model of the Vicchio stele with its four inscriptions highlighted.

Scholars are still in the process of deciphering and translating these inscriptions, and are using new digital techniques to assist them. Three-dimensional models of the stele made through photogrammetry and laser scanning have allowed the surface of the stone to be examined in minute detail, especially using various simulated light conditions. These help identify letters that would normally be invisible to the naked eye, leading to the identification of four different inscriptions on the stele.

The inscriptions consist of four texts written at different times. Of these, only the most recent can be read with any certainty. It is written in a pseudo-boustrophedon style (Greek for “as the ox turns”): One line goes in one direction and another reverses course, much as an ox plows a field. Later, part of this inscription was erased and reinscribed. It can be translated as follows:

“Of Tinia [or ‘for Tinia’] in the place (thanuri) of Uni two [objects] were dedicated.”

3D model of the Vicchio stele with the translated inscription naming Uni and Tinia highlighted.

Here, the inscription names the two great Etruscan gods: Tinia, the equivalent of Roman Jupiter, and Uni, the rough equivalent of Roman Juno. The reference in the inscription to Uni, who was closely connected to fertility and childbirth in the Etruscan world, indicates that the goddess was the titular divinity for the sanctuary.

All the texts on the stele seem to be sacred in nature, and they include words that can be translated as “dedicate” or “donate,” making it a living archive of the sanctuary’s religious activities. Scholars are continuing to study the stele and its inscriptions in the hopes of further deciphering the Etruscan language and understanding more about religious practices at Poggio Colla.

Modeling the Stele

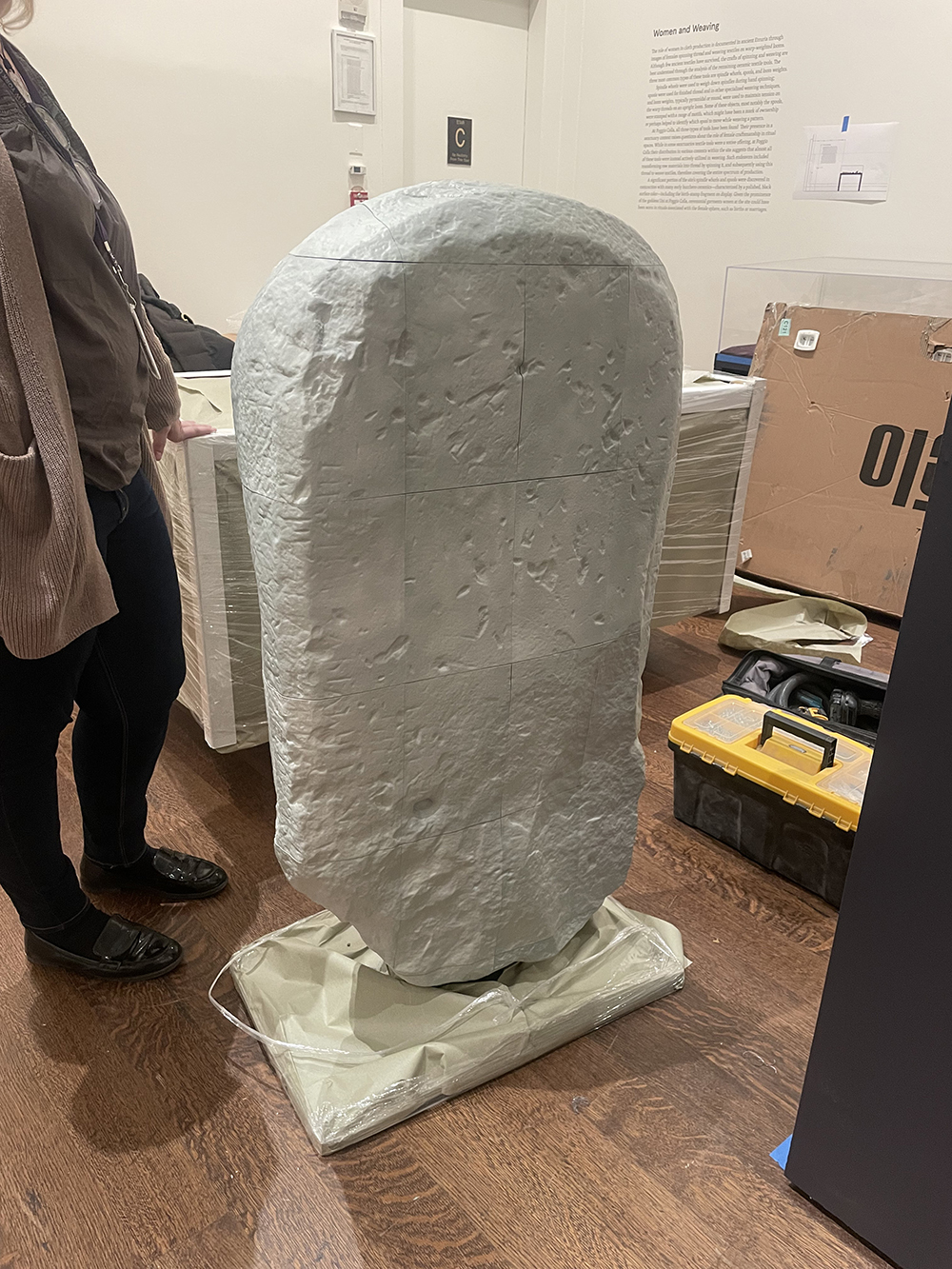

The exact, life-size (1:1 scale) replica of the Vicchio Stele was produced using state-of-the-art digital techniques involving high-resolution 3D scanning and printing. The original artifact, housed at the Fondazione Luigi Rovati in Milan, was digitally recorded by Duke University’s DIG@Lab using a sophisticated RangeVision Spectrum structured-light scanner (INKAY Technology).

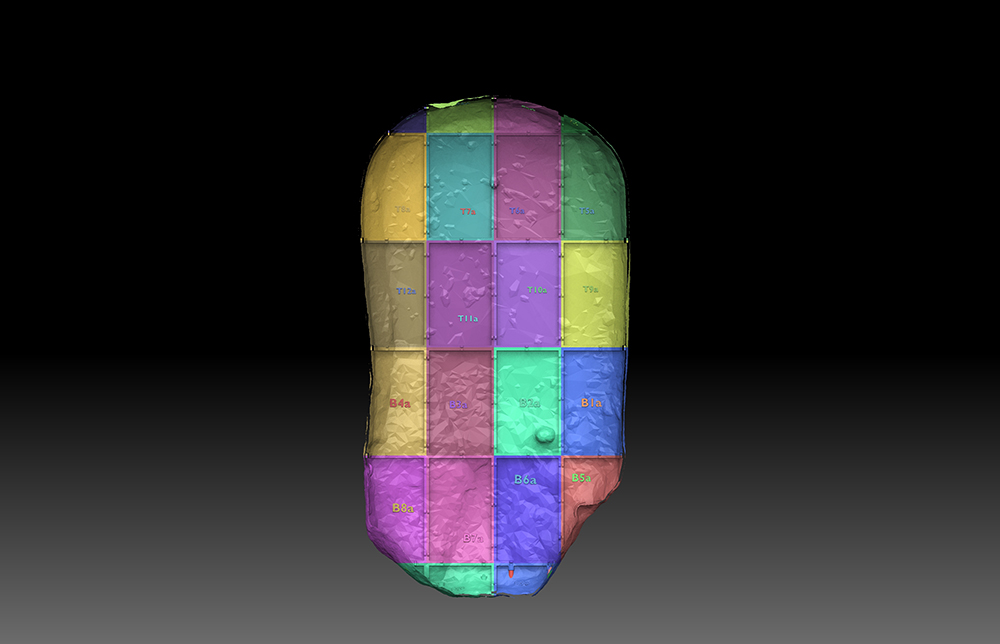

3D Model of the Vicchio Stele, as segmented for printing by the LaGuardia Studio.

Researchers combined thousands of individual scans into one complete digital model, carefully refining and cleaning the data to ensure maximum accuracy and fidelity to the original artifact. This scanner projects intricate patterns of light onto the artifact’s surface, precisely capturing even the smallest details and resulting in a digital model with around 20 million vertices and 40 million faces.

Printing

To produce the full-scale 3D-printed Vicchio Stele, the LaGuardia Studio (LGS) began with the high-resolution 3D scan of the original artifact made by DIG@Lab. The digital model was then segmented into around forty-five individual parts using the software NetFabb, optimizing for both print efficiency and structural integrity. Using ZBrush software, internal ribs and custom fastening features were added to create stable, interlocking connections between pieces.

The components were fabricated using LGS's HP’s Multi Jet Fusion (MJF) 580 printer, a powder-based additive manufacturing process known for its precision and durability. In MJF, a fine layer of nylon powder is spread across the build platform, and fusing and detailing agents are selectively jetted onto the surface. Heat is then applied to solidify the chosen areas, building the object layer by layer. This process produces highly detailed parts with strong mechanical properties and a smooth surface finish. This meticulous workflow, from digital modeling and engineering to advanced fabrication, enabled the successful realization of a complex, full-size stele that faithfully preserves the intricacy and presence of the original.

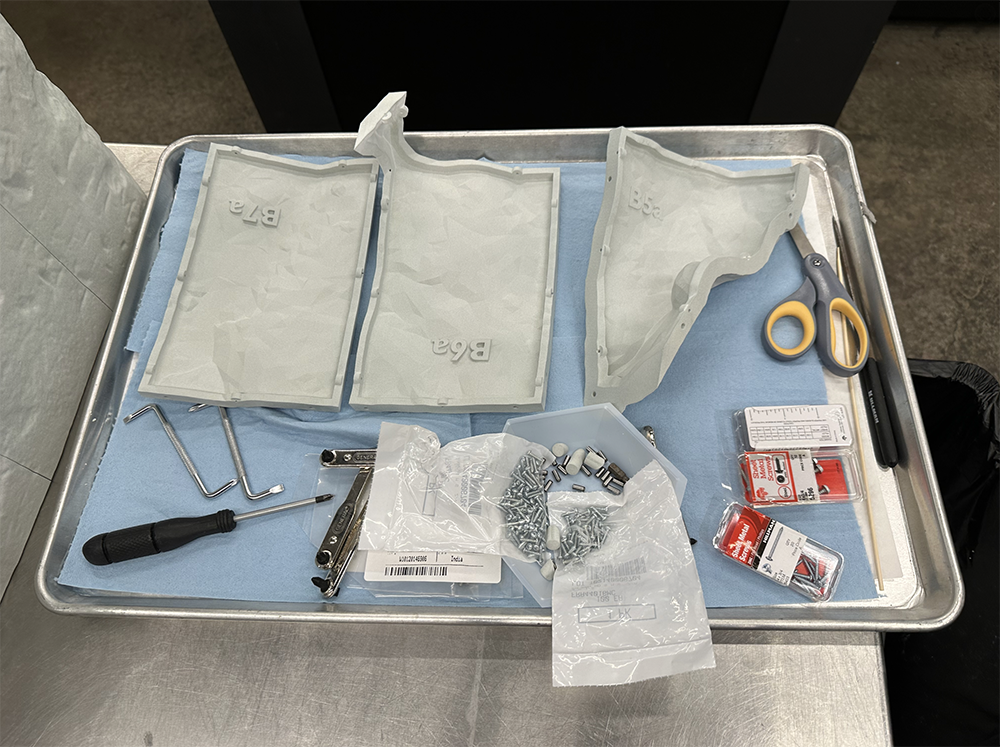

Labeled assembly instructions for the stele pieces made by LGS.

Assembling

After the pieces were printed, they were assembled by Contour Woodworks. The team at LGS labeled each piece of the print individually, and provided an assembly guide to make the process run smoothly. Pieces near the top of the stele were labelled “T,” and pieces on the bottom half with a “B.” Each piece had a corresponding mate, designated by lowercase a’s and b’s: Piece T2a would be attached to piece T2b, and so forth.

To stabilize the printed model, the Contour fabricators used a two-part epoxy and small screws. They then sealed the finished product with three coats of a resin varnish to ensure it could be touched and cleaned safely. The replica was then sent to ISAW to be installed on a podium where it can now be seen in the gallery.

Test assembly and materials. Copyright LaGuardia Studio.

AI Rendering of the Sanctuary and Landscape

Through the use of AI, archaeologists and historians are able to make ancient sites more understandable, meaningful, and visually compelling, bridging the gap between the past and audiences today. AI can synthesize enormous datasets—archaeological plans and environmental reconstructions—to produce highly realistic and detailed visualizations. These visuals make material history] accessible and understandable for a wide audience. AI efficiently combines data that would take humans much longer to analyze manually, ensuring a reconstruction rooted deeply in scientific evidence.

AI renderings of the Poggio Colla temple. Copyright of the Institute of the Study of the Ancient World.

However, AI-generated reconstructions can also introduce inaccuracies, such as overly precise details, assumptions not fully supported by archaeological data, or abstracted, stylized, or incorrect details. Therefore, while valuable, these visualizations should be interpreted critically and continually refined as new evidence becomes available. For example, the first AI renderings of the Poggio Colla temple resembled a Greek Doric temple and had to be modified by the team at Duke to more closely resemble Etruscan temple architecture and the temple plan from the site.

The AI-generated reconstructions of the ancient temple of Poggio Colla and its surroundings were generated by the team using Open AI ChatGBT 4.5 in combination with Sora. They combined archaeological findings, palaeobotanical studies, and paleoenvironmental analyses to reveal the complexity of the ancient landscapes and ecosystems. Archaeological excavations provided a small amount of data on the size and construction of the temple—with a significant amount of uncertainty—while analysis of ancient pollen and seeds allowed researchers to accurately restore the vegetation and agriculture of the landscape. AI technology was crucial because it efficiently synthesized these complex and extensive datasets into a realistic, detailed visualization, enhancing accuracy, speed, and interactivity. Such visualizations help scientists test hypotheses quickly, offer new insights, and allow the broader public to vividly imagine ancient life, strengthening our understanding of cultural heritage and historical interactions between humans and the environment.